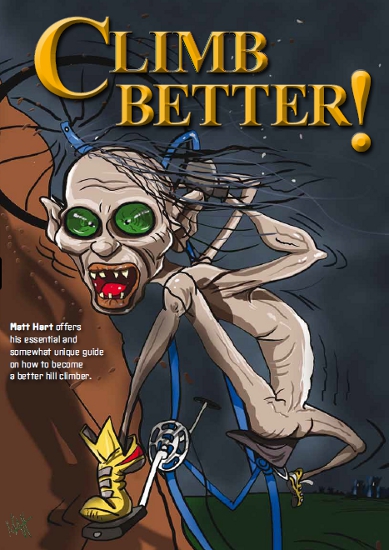

When someone says they’re a ‘good climber’ it kind of conjures up a suggestion of mystique and fantasy with me? What is a good climber? I have an image etched into the creative side of my brain of some kind of supernatural, lean, ripped, if not slightly unhealthy-looking character with body fat so low that you can see the blood coursing through its veins. Perhaps the closest visual specimen I could suggest (to which you could relate) would be Golum from the Lord of the Rings trilogy…

I have a vivid imagination of course, but I’m also a scientist, so overriding the feelings I have in my gut with an intelligent, logical set of rules comes just as easily to me. So sadly, if you were enjoying my whimsical ramblings, it has to come to an end, because being a good climber is actually just about three things:

- Your bodyweight

- The weight of your bike and equipment

- Your power

If Golum did exist, perhaps he would be both powerful and light in his own mythical way, but the fella can barely stand on two legs, so the chance of him being able to power a bicycle is quite frankly out of the question. I reckon his immune system would prevent him from ever realizing greatness anyway, because he always seems to be coughing and sneezing when I’ve seen him.

I guess what I’m trying to say in a very protracted and odd way is that a great climber isn’t mysterious; they simply have a good power-to-weight ratio. Let’s look at the three points listed above separately and make sense of it all:

- Bodyweight: Light people go up hills faster, because they’ve got less weight to shift against gravity, it’s as simple as that. A good experiment to carry out if you think my opinion lacks credibility is to find a big hill near where you live and ride up it as fast as you can (after a sensible warm up of course) and time yourself from start to finish. Then go to your local supermarket with a large rucksack and fill it with tins of beer. Pay for it obviously, and then ride gently to the bottom of the afore mentioned hill and repeat the experiment. You should notice that you’re quite a bit slower on the second effort. If you can’t be bothered to get your bike out to do this, although I stagger to think why you’d be reading this magazine if you weren’t, you could do the same experiment in your car, but you’ll just need to purchase a lot more beer!

So there’s a lesson here for people who want to ride up hills quicker, which is the less weight you carry up a hill, the faster you’re going to go. I used beer as my ballast example for obvious reasons, as this is one of the culprits responsible for many people carrying too much body fat in modern society. It’s not quite a linear response. Every tin of beer you drink won’t increase your bodyweight by the mass of that tin, but creeping obesity is a huge problem in the western world and if you’re consuming a few hundred calories per day that you’re not burning off, your body fat levels will sneak up (and your climbing prowess will sneak down).

Beer isn’t the only weight gain demon, there are a multitude of calorie sources that will get stored as body fat if you don’t use them, so this might be a good time to enlighten you about the ‘energy balance equation’. The problem is that weight loss, or rather (politically) ‘body weight management’ is made ever so complex by the multi-million dollar dieting industry. Aggressive dieting corporations will have you believe that if you consume a diet of Chinese goat urine for breakfast, lunch and dinner – this will work wonders as long as you don’t forget to ingest their ‘special and expensive’ milk shake once per day whilst standing on one leg, facing north and praying to Pavarotti, the god of slenderness.

The energy balance equation on the other hand says thus:

- If energy (calories) coming in to your body are greater than the ones being used up by your basic metabolism + the exercise you do, you will PUT ON weight.

- If energy (calories) coming in to your body are less than the ones being used up by your basic metabolism + the exercise you do, you will LOSE weight.

- If energy (calories) coming in to your body equal the ones being used up by your basic metabolism + the exercise you do, you will STAY THE SAME weight.

What’s interesting is that I have studied Sports Science at Degree level for 3 years, worked for 10 years in Health Clubs in central London and coached and consulted for just as much time with numerous athletes (including those at world class level) and weight management (losing weight) essentially comes down to ‘eating less and exercising more’. It’s not rocket science and it never has been, so don’t believe the hype and part with your well-earned cash for a ‘clinically proven’ weight loss solution. The poof will undoubtedly have been messily extracted from a university study where some post grad student heavily influenced by intoxicating liquor will have been paid off to say absolutely anything, if indeed the study exists at all. Or, simply the weight loss solution has revolved around ‘negative energy balance’ anyway and this can be achieved easily without drinking goat’s urine and all the other stuff.

Beer has been mentioned a few times already in this article, so now I shall mention it again. Did you know that alcohol contains 7 kCals per gram and that you have to store these calories as fat before you can release the energy? This makes it worse than dietary fat, which is more energy-rich at 9 kCals per gram, because at least with the fat from your food, you’re able to metabolise it whilst it’s surging through your vascular system looking for somewhere to call home. Carbohydrate and protein are both 4 kCals per gram, so have the lowest energy density out of all the nutrients, however it needs to be noted that any calorie consumed in excess of your energy output for that day will be stored as fat.

Now consider that 1kg of fat is 9,000 kCals, so if you have a positive energy balance of 500 kCals per day (which is quite easy to achieve) it will take you 18 days to put on a Kg in body weight. By the same token, if you want to lose weight, a negative energy balance of 500 kCals per day will result in a weight loss of 1 Kg in 18 days and what never ceases to amaze me is that people will allow weight to creep on at about 1Kg per month, but when it comes to losing it, they want to lose a kilo per week! The message here – if you want to lose weight and climb hills faster, take your time in losing the body fat – don’t be in such a rush and you’ll get there.

- The weight of your bike and equipment: I don’t think we need to spend to much time on this point do we? It all makes sense doesn’t it? However, before you go out and spend your inheritance on the latest XC race whippet-engineered bike to save weight, do please consider point 1 above. If you’re carrying a few kilos of extra lard, start by getting out on your existing bike a bit more, increasing the intensity of your exercise sessions and cut back a bit on the calories. You can then put all the money you’ve saved on food aside and buy yourself your dream bike once you’ve reached a bodyweight where you can really do it justice.

So, what should this dream bike be? I know that Mountain Biking has now shifted into a world of gravity endurance and trail riding, in which case I’m sure you have chosen the perfect bike for your discipline, but if you’re an endurance rider and climbing hills efficiently and quickly is an important part of your discipline, you will ascend much more slowly if you ride an over-engineered bike. With a bit of practice, you can improve your bike handling and descending on a lighter bike with shorter travel – even dare I say it on a ‘hardtail’. I’ll refrain from being a geek and going into deep and vivid detail on how to keep the weight down on your bike, because there are plenty of interesting experts on internet forums who can advise you better than I (and quite frankly have the time to worry about it), but going tubeless on the tyres and having a nice light set of wheels can make a noticeable difference.

I have one final bugbear and it is this. At which point should you carry a backpack and when should you leave it at home? I think that there are far too many Mountain Bikers out there where the boundaries are unnecessarily blurred. For instance, if you’re in a team of 4 riders at a 24 hour endurance race and you’re taking it in turns to do laps, why on earth would you wear a backpack? Often they’re quite big backpacks too. I can understand why these people might want to take their bladder with them for rehydration, although fitting a bottle cage to your bike and attaching a 500ml bottle would be more than adequate in this kind of situation, but what’s in the rest of the pack? Do they take a full survival kit out with them or something – or a spare fold-up bike? I really am curious. In most cases, it probably ends up being a kind of Mountain Biker’s handbag, full of random stuff that he or she might need in case they experience a really obscure situation. Bomb disposal perhaps?

I actually don’t ever wear a backpack (as you may have guessed after my anti-backpack rant), except when I’m guiding and have to carry spares/first aid kit to ensure other’s welfare, so I guess I come at this from a slightly biased angle, but think if you are a backpack fetishist, please think about the WEIGHT. It’s a lot of stuff to carry up every hill you encounter (even the empty backpack will be quite heavy). Slim it down – that’s what those three pockets are on the back of your jersey are for, and you could always fit a little saddle bag if you run out of space.

- Your Power: Again, if we consider the ‘car being driven up a hill’ scenario, imagine completing the second test, when the car is full of beer, but in a different car? Imagine a car with jet engines and rockets attached to it, yet still full of beer. This contraption will ascend the hill in a fraction of the time it would take the empty car, despite being filled with beer ballast, because it has significantly more POWER. Apologies for the perhaps condescending example, but I mention this because I’ve lost count of the number of times that someone has said to me that they’re not a very good hill climber and that they therefore need to practice riding up hills. Whilst this may seem like the common sense thing to do – to practice the skill you’re not so good at – there’s actually not a huge amount of logic in it other than the repeated bouts of intensity will increase power over time. I maintain that you will go significantly faster up hills if you consider seriously points 1 and 2, discussed earlier on and then consider ways of increasing your power as a separate entity. This means that you could train your power on the flat and then when you do reach a situation where the land tips upwards, you will, I assure you, ascend quicker than you did before.

Boosting your power is rather a wide subject though, because some of us have good short term anaerobic power, so can ascend short hills quickly and others have a higher sustainable power, which benefits them on longer, more drawn out climbs. If you want to be a true master of hill climbing, you should work on both the aerobic and anaerobic energy systems, because this will give you the versatility to ‘snap’ and conquer a short hillock and also be able to master the longer, more tactical climb where pacing yourself will be key.

For the anaerobic ‘snap’ you should consider three different types of high intensity intervals for your training:

15-Second Intervals: This type should involve only 15 seconds of explosive power followed by a long 3-minute rest. This trains an energy system called the ‘Phosphocreatine’ system and you need the long rest between intervals to allow the system to regenerate itself. Cutting down the recovery between these intervals is actually a bad thing to do, so don’t rush this session. Start with 6 intervals and work up to as many as 20 if you can find the time.

1-Minute Intervals: These are 1 minute long with a 2-minute recovery between them. Pace yourself so that your power output is as even as possible throughout the interval, but by the time you’re into your last 10 seconds, it should hurt very much! Start with 4 of these and work up to 10 as you get fitter.

2-Minute Intervals: These are 2 minutes long with a 1 minute recovery between them. Again, pace yourself and try to keep an even distribution of power throughout the interval. Start with 4 and work up to 8 repetitions over time.

The first type of interval could be combined with the second or third types of intervals in the same session, but don’t combine the second and third types. As a suggestion, choose 1 day per week and have a 2 week rotation so that you complete first and second types in week one and first and third types in week two.

Where do you perform these? Well, you could find a hill to ride up and down, there’s nothing wrong with that, but you could just as easily complete these on an indoor trainer or exercise bike and they’ll have the same power-boosting effect.

For aerobic power, or more precisely ‘anaerobic threshold power’, you need a different kind of interval. These intervals are more prolonged with shorter rest periods and here are two examples:

5-Minute Intervals: Just as the title states, ride hard for five minutes, then go easy for one minute and repeat. Start with to 2 and work up to 6 repetitions as your fitness progresses.

10-Minute Intervals: These are the same as above, but the interval is longer and you are rewarded with a 2-minute recovery. Again, start with 2 and work up to 4 repetitions over time.

Again, you should perform one of these sessions once per week, preferably at least 2 days apart from the higher intensity interval session. Do the 5-minute intervals one week and the 10-minute ones the next.

In closing this article, I hope that in addition to learning how to become a better hill climber, you’ve also learnt valuable lessons on why certain members of the cast of Lord of the Rings will never be able to train as consistently as you, why it’s inefficient to drive your car fast up a hill with a trunk full of beer and (hopefully) how useful it would be to do a bit of housekeeping on your backpack. Who knows what you might find? You might find the ring ‘my precious’…

Article originally produced by TORQ for Mountain Biking Australia late 2012. Many thanks for their kind permission to use the picture at the start of this article. For further information, visit www.bicyclingaustralia.com.au