It is without doubt that exercise will enhance your immune system making you less likely to pick up a bacterial or viral infection and it puts you in a better position to fight it if you do, but how much exercise does this need to be?

A small amount will have little effect and too much may weaken your immune system making you more susceptible to infection. Research suggests that there is also a window, particularly after heavy exercise where an athlete is most vulnerable and immune defences are suppressed, so it would be pragmatic to consider your behaviour around this window if you are going to benefit fully from the immune-enhancing benefits of exercise.

There are a variety of ways in which exercise is thought to improve immune function:

- Exercise causes enhancements in antibodies (white blood cells), which the immune system uses to fight disease and an increase in what researchers term ‘immunosurveillance’ meaning that illnesses are detected earlier.

- The rise in body temperature whilst exercising may prevent pathogens from developing and multiplying, in a similar way to a fever is the body’s response to infection.

- Moderate exercise slows down the release of stress hormones, which may protect against illness. Although this is not necessarily the case for heavy exercise, there are interventions we can implement to support the immune system if exercise load is more than ‘moderate’, which we discuss in the Fuelling, Recovery & Immunity section.

- Physical activity may flush pathogens out of the airways at an early stage, stopping a pathogen from taking hold. Please note that this is theory as to why you may be less likely to get infected as a result of exercising regularly. Exercising with a known infection could make your situation much worse and if you are showing any symptoms, it’s too late and you should stop exercising and rest.

- Cardiovascular exercise produces an antioxidant generated from the muscles called ‘EcSOD’ which may protect the cells of your body against infection. This is cutting edge research and further insight is provided in the last paragraph on this page.

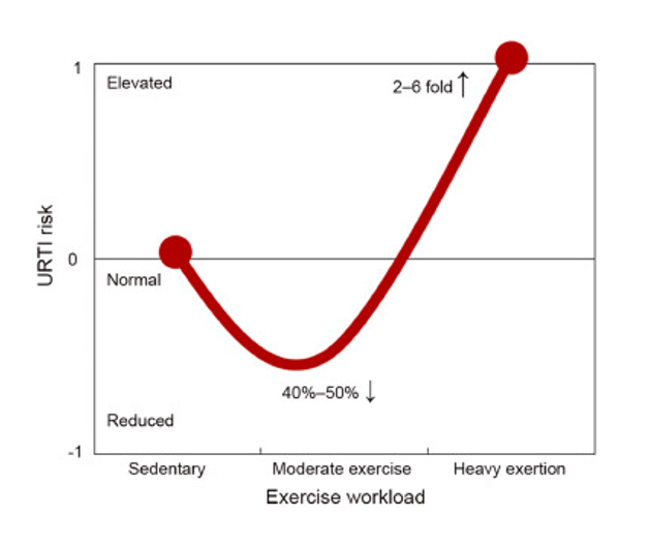

Some research suggests however, that the amount of exercise performed is important. If one were to consider sedentary individuals as the baseline there is certainly evidence that moderate exercise boosts immune function, yet heavy prolonged exercise may put you at higher risk of picking up an illness than a sedentary person. This is displayed in the J-shaped curve below.

Diagram above from: Nieman, D.C. 1994. Exercise, Infection, and Immunity. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 15(S 3), pp.S131-S141.

According to a recent (2019) review paper by Nieman and Wentz in the Journal of Sport and Health Science:

“…moderate and vigorous exercises are differentiated using an intensity threshold of 60% of the oxygen update and heart rate reserve, and a duration threshold of 60 min.”

We’re not quite sure how to interpret this, but it’s probably a fair assumption to suggest that exercise under 1 hour in duration at a steady state is considered moderate. We would also make the assumption that a short 30-minute bout of intense exercise like interval training could also be termed moderate, because although it would be intense, it would not be particularly protracted and therefore not overly draining to one’s physiology. This is however our interpretation of Neiman and Wentz’s words.

None of this for a moment suggests that you shouldn’t exercise for over an hour, you just need to take appropriate precautions, as we will discuss shortly. Also, it’s a reasonable assumption to make that recommendations should be perhaps relative to the fitness of the individual – moderate for a highly trained athlete isn’t moderate to a person who has always exercised for leisure.

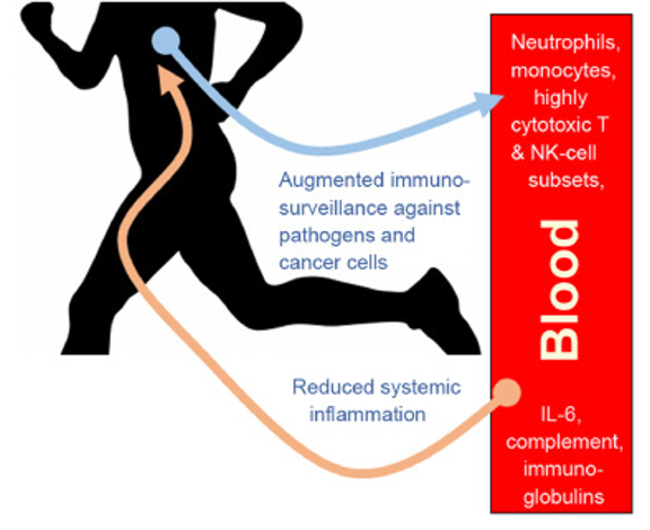

This same review paper sums up the benefits of moderate exercise in the diagram above, suggesting a feedback mechanism of increased immunosurveillance (the ability and speed to detect pathogens) along with a reduction in systemic inflammation – in other words, the cells of the body are kept in better shape by exercise so they are less susceptible to infection.

The j-shaped curve above suggests that heavy exercise pushes the body into the realms of immunosuppression and whilst this doesn’t mean that you should avoid heavy exercise, it means that as with most things, knowledge is power, and if you’re aware that your immune system could be compromised at a particular time, you can take steps to protect yourself. Pederson et al found during a study in 1998 that high load exercise reduced the quantities of antibodies responsible for fighting infection and that a 4-hour post-exercise window exists where the body would be particularly susceptible to infection. Therefore, if you’re going to go for a big bike ride, keep yourself to yourself for 4 hours afterwards and certainly don’t go out to the supermarket.

On the other hand, another review paper by Campbell & Turner (2018) puts forward the argument that ‘all exercise is good’ and that any immunosuppressive disadvantages are outweighed by the longer term immune-boosting benefits of regular exercise regardless of intensity or duration. Also, researchers often struggle with an interdisciplinary approach, so we need to consider all variables – for instance, in the Fuelling, Recovery & Immunity section of this resource, we discuss the role that carbohydrate fuelling plays in supporting the immune system during heavier exercise bouts and interventions like this cannot be ignored. Also, we refer you to the last paragraph on this page where a cutting edge scientific review is discussed in relation to an antioxidant substance called EcSOD produced by the muscles during exercise, which is thought to assist in immunity.

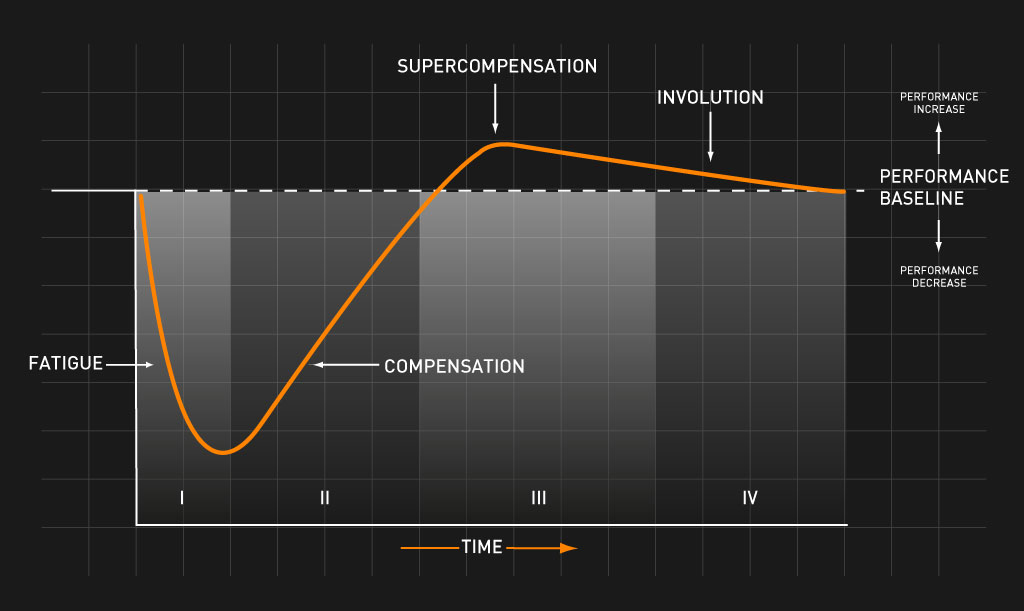

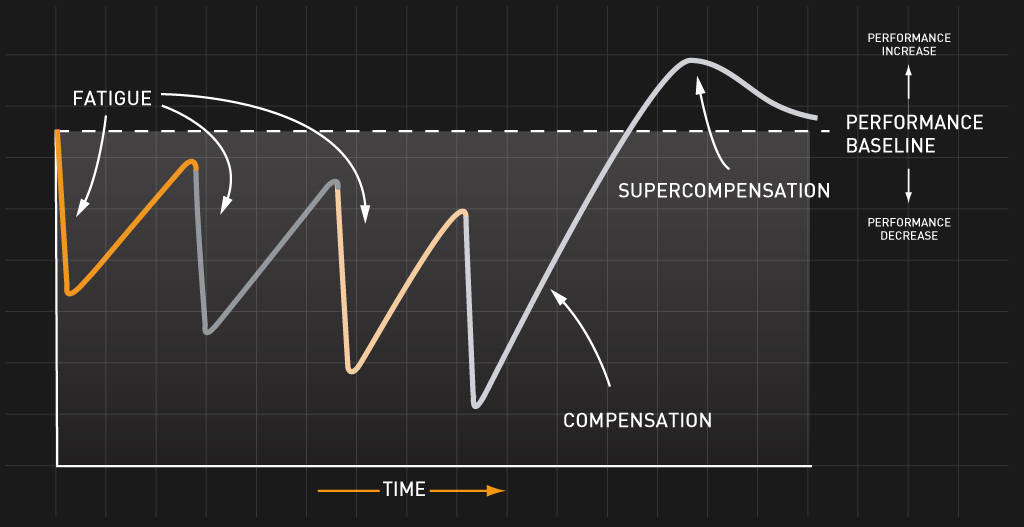

At TORQ, we are forever the pragmatists and therefore, of course, we have an opinion on this. The curve above indicates how the human body adapts and responds to exercise and we discuss this concept in greater detail HERE. Effective training requires periods of hard work and recovery to allow your body to adapt and get stronger and in the long term you should expect similar adaptations to your immune system. This doesn’t mean however that there aren’t going to be points in time where you are likely to be weak and immunosuppressed and certainly observing the 4-hour window after a heavy bout of exercise would be a sensible route to take.

Similarly, if you ramp up your training over a number of days to overload your physiological systems – a well-recognised strategy to peak for an event or competition – you are likely to put your immune system into a more vulnerable position and you should adapt your behaviour accordingly. Perhaps socially distancing yourself over this period would reduce the risk of getting sick before the important event? We would suggest that your immune system would behave similarly to the rest of your physiology during a high load peaking cycle. You could push yourself to an overall low point through cumulative heavy training sessions and then recover to a supercompensated high point after a period of rest/recovery where germs might literally bounce off you! The trouble is, you don’t know at which point along this cycle you might meet the pathogen.

Exercise and Covid-19: At a time like this when there is a particularly dangerous infectious virus prevalent in the community, we would recommend that on the whole with competitions cancelled, you should be considering how best to use exercise as a tool to strengthen your immunity. Everyone will have a different level of physical conditioning at the moment, but a move to incorporating more recovery time, observing the 4-hour window and not stacking up unnecessarily high training loads would make sense to us.

Interestingly, a recent review (April 2020) by Dr Zhen Yan of the University of Virginia School of Medicine has demonstrated that “medical findings strongly support the possibility that exercise can prevent or at least reduce the severity of ARDS, which affects between 3% and 17% of all patients with Covid-19.” ARDS or Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome involves inflammation of the lungs causing difficulty in breathing and the likelihood of the patient needing to be put onto a ventilator. Dr Yan’s in-depth review of existing medical research drew a correlation between an antioxidant known as Extracellular Superoxide Dismutase (EcSOD), which is produced by the muscles during cardiovascular exercise. This antioxidant neutralises substances called ‘Free Radicals’ protecting against infection. We cover free radicals and antioxidants comprehensively later in this resource in the section Fighting an Infection with regard to Vitamin C.

Read the full review, which is supported by the National Institutes of Health, by clicking HERE.